Ecology in the Field: Bromelania!

The second day here at Las Cruzes, Peter tasked us each individual to a 20 minute walk around the immediate area to conjure up a set of ecological questions at various scales: individual, population, community, and landscape. Beyond that structure, whatever came to mind was allowable in this game of organized wondering. Within moments of my solo walk, I came upon this lizard (not my picture), ameiva festiva, Costa Rica’s only whipped tailed lizard, I later learned.

I remember coming upon whipped tail lizards in New Mexico as a kid, many missing their tails. So I ended up spending my full 20 minutes with this one lizard and instead of thinking about how I could catch it, like I did when I was a kid, I started asking questions about its diet preferences, how much it had to eat to maintain such high metabolism, etc. I wondered how the lack of a top predator in the ecosystem (jaguar) has effected is abundance, does its range include some of the habitats undergoing restoration and how might it contribute to that restoration. I won’t bore you with all of the questions, but the one I settled on to bring back to the group was a curiosity about the way the lizard’s metabolism, ability to hunt and mate was affected when its tail was sacrificed. The lack of tail might compromise its movements in significant ways and at the same time growing back that tail takes energy itself. Limited resources would be allocated differently but would the lizard be more or less conservative in its hunting and might it forgo mating-related activities altogether? Many of these questions if not all are surely answered in the scientific literature, but I found the exercise both enlightening and quite a lot of fun.

The walking exercise is now being put into practice at a different scale: we’ve broken up into teams and pursuing a single research question. My team in particular is trying to establish whether the microbial community in a bromeliad is facilitated by the plant itself in some way. Does that sound fascinating? Well, like all things, you get close enough to it and it absolutely is. Totally fascinating. I’m on the sub-team that’s ironing out the experimental design. Our aim is to both describe the micro community in terms of richness and abundance of species and then conduct an experiment where we compare a bromeliad plant (neoregelia carolinae) to a “cup of water” to see if there’s something about the plant itself that facilitates community development. All in 3 days of work.

So far, our plan is going well. We’ve identified a total of 30 individual plants to work with (conveniently located here in the Wilson Botanical Garden) and described the community composition in a set of 10. For the experimental component (a manipulation of nature to make a point!), we extracted the contents from center column of the other 20. In ten of those we filtered the contents through tight mesh to remove the micro-community and returned the remaining water, with its “natural” chemistry, to the plant. In the final ten plants, we removed the contents and replaced it with rain water. Here’s one of my teammates extracting the water-based community from one of our experimental bromeliads.

We next set up a set of controls: plastic cups interspersed in the field of bromeliads. We cut holes all to give them a comparable volume to that of our average bromeliad and then broke them into groups containing either rain water, rain water with a “swish” of the filtered bromeliad water (to control for limitations in extracting all of the community from the bromeliad plants), or filtered bromeliad water as in the plant treatment above. Then we let the whole experiment “cook” for several days.

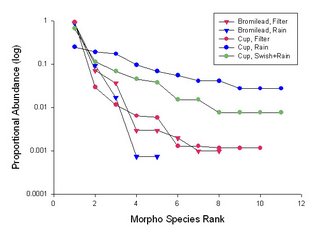

Yesterday was spent at the microscope. I haven’t looked through a microscope in any kind of serious way since high school! But there we all were with micro community taxonomy texts on hand separating and counting ostracods, mites, branchipods, midges, nematodes, copepods, mosquito larvae, and sorts of tiny spiders, ants, bees, flies and even a cricket. Moving from the microscope to the computer we are in the midst of analysis to compare the biodiversity (measured in our case as “evenness”: the number of difference species and abundance of each species) in each of the treatments. If our hypothesis holds out, we should see more diversity in the plants versus the cups and more diversity in the “naturalized” water over the plain rain water in both plants and cups. Here’s one view of our draft results, a “rank-abundance” which gives a graphical view of both richness (number of different species) and abundance (number of each species). Turns out there was too much variance between the results from each treatment type for our study to be considered valid, but we did see a pattern in the direction of evenness for the cup treatments and species dominance in the bromeliads.

My teammates have brought extensive expertise to bear on the project. It’s going to be interesting when I have to do an ecological study all on my own in a few weeks.

Labels: Ecoinformatics, Healthy Planet

4 Comments:

I am really interested in the whipped tailed species. Is it true that this particular species is all female and all they need is stimulation to reproduce rather than actual penetration? I read this on Yahoo and have been researching and cant find any information.

Those are some wonderful pictures of Bromelania. I'm also wondering about whipped tailed species question that kyra asked.

Whip-tailed lizard females have the ability to reproduce through parthenogenesis and as such males are rare and sexual breeding non-standard.

Too much variance to be valid? Actually if you have sufficient replication and the variability swamps ability to detect differences, then you conclude that differences were not detectable. Sounds valid to me! And if you need a million replicates to detect differences then the differences are probably biologically unimportant.

Post a Comment Hide comments